No Accusation Does Not Equal Innocence: Rethinking the German Soldier in WWII

In public memory, a dangerous myth continues to resurface: “If a German soldier wasn’t accused of a war crime, he didn’t commit one.” This belief, whether stated outright or implied, obscures the uncomfortable truth of how the Nazi war machine and Nazi state functioned. While not every German soldier participated directly in atrocities, the absence of a war crimes charge does not automatically indicate innocence. In fact, most perpetrators of Nazi violence were never prosecuted, despite widespread complicity. Let’s explore why that is, and why it matters.

Legal Differences

To start, we need to clarify a few things related to war crimes. The terminology matters. Let’s drive right in.

Suspected of a War Crime

When someone is suspected of a crime, this means that there is reason to believe, some evidence, or information suggesting the person may have committed a war crime. Suspicion alone is not evidence of guilt, but it’s a starting point for investigation. For example, Allied investigators suspected many German officers of ordering reprisals but lacked the documentation to proceed legally.

Implicated

Someone who is implicated is linked or connected to a crime without formal accusation or legal status. For example, it might be a Wehrmacht officer whose unit was present at an execution, but who was never investigated. Unit records might place them at the scene of the crime, but there has never been a followup.

Accused of a War Crime

An accusation is “a charge of wrongdoing”, which means that the suspect becomes involved in the legal process.1 Being accused of a war crime means that the case has moved beyond suspicion. The person suspected now becomes involved in a judicial process. But importantly, this doesn’t mean guilt has been proven. The presumption of innocence still applies until there’s a conviction.

Convicted of a War Crime

According to Merriam-Webster, conviction is defined as this: ”1: the act or process of finding a person guilty of a crime especially in a court of law”. 2 The person has been convicted and can be punished for the crime. To be convicted, there needs to be evidence and a trial.

Complicit in a War Crime

Someone complicit was involved in the crime, but might not have directly carried it out.3 This is different than a direct perpetrator, who carried out the crime. A Wehrmacht driver driving prisoners of war to an execution site can be an example of someone complicit in a war crime. He might not have carried out the crime, but he did enable others to do it.

Perpetrator

A perpetrator is the person who directly carries out the crime, which is different than someone who is complicit.4 A perpetrator might be a Waffen-SS soldier carrying out the execution of prisoners of war. This is the person pulling the proverbial trigger.

Acquitted

The individual was tried in a court and found not guilty. However, it is important to note that acquittal does not necessarily mean the person was innocent. It just means that the evidence was insufficient for conviction beyond a reasonable doubt. Some defendants at the Nuremberg Trials were acquitted on certain charges despite involvement in the Nazi regime.

Facilitator

Facilitators made the crime possible. This can be through logistics, looking the other way or administration. Think of the civil servants who organized the train schedules, which then carried people to extermination camps. They might have just been doing their job, but in the process they facilitated the extermination of others.

Pardon

Similarly, a person who is pardoned of a sentence, is still legally convicted of the crime. A pardon can be done for pragmatic or political reasons. They don’t erase the crime, just the legal consequences.

Systemic vs. Individual Crimes

A systemic crime is different than an individual war crime. A systemic crime is one carried out by policy and institutions. An example could be the Holocaust, where millions of people were systemically murdered by the Nazi state. An individual war crime could be the execution of a group of Soviet prisoners of war by a group of Wehrmacht or Waffen-SS soldier. However, individual crimes can still be part of a systemic crime.

Innocent Until Proven Guilty

In legal systems based on the rule of law, individuals are presumed innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. This is a foundational principle of modern justice and ensures that people are not punished without due process and evidence. However, this legal standard does not mean that someone is factually innocent, it simply means that guilt was not proven beyond a reasonable doubt in a legal setting. In historical analysis, it is important to recognize that many individuals involved in systemic crimes were never brought to trial, and thus their legal status remained untouched, not because they were innocent, but because justice was incomplete or never pursued. Legally being innocent is not the same as exoneration. Silence in the historical record reflects gaps in justice, not necessarily virtue, and it has become an excuse to ignore history. Saying “we don’t know what this officer did, so let’s assume they did nothing wrong” isn’t neutrality, it’s erasure.

Why These Distinctions Matter in Historical Discussion

Not being convicted of a war crime, does not mean someone is innocent. Many German officers were never tried. Sometimes this was due to lack of evidence, but it could also be pragmatism or political reasons. Others have been accused, but were acquitted. A large number of military and civilian officials were administratively essential to war crimes, meaning they were complicit, but never prosecuted. Lastly, suspicion was often left uninvestigated. The vast scale of Nazi war crimes meant many suspects were never formally processed. In my book Tragedy and Betrayal, there is Walter Bartels, who was complicit of war crimes, but never sentenced, because other cases were deemed more urgent.5

The Challenge of Evidence and Fact-Finding in War Crimes

Prosecuting war crimes isn’t just about establishing guilt, it depends on the ability to uncover facts and prove them with credible evidence. This process faces unique challenges in the context of war. Evidence is often lost, destroyed, or deliberately concealed. For instance, as Allied forces approached extermination camps, the Nazis systematically burned documents in an effort to hide the scale of their crimes.

Successful prosecutions also depend on witness testimony, which may be unavailable or lost over time. If all victims are executed and no one survives, there are no eyewitnesses to testify. The Peleus War Crimes Trial, in which German U-boat U-852 surfaced and machine-gunned shipwreck survivors, only occurred because three men lived to tell what happened. Without their survival, there might never have been a trial.6 War crimes trials often took place years or even decades after the events. Memories fade, witnesses die, and physical records deteriorate. In some cases, political pressures, especially during the Cold War, impeded investigations or shifted legal priorities. Together, these factors mean that even well-documented atrocities may never result in charges or convictions, not because the crimes didn’t happen, but because they couldn’t be legally proven in court. Combined with the sheer number of suspects, which the courts couldn’t handle, many German soldiers were never tried, although they might have been involved in war crimes or systemic crimes.

Criminal Orders and Systemic Violence

The reason why the German armed forces were all potentially complicit in war crimes, is because of the criminal orders. The Wehrmacht (German army) operated under explicit orders from the Nazi high command. These were not vague suggestions but codified directives that laid the legal and moral groundwork for mass violence: The Commissar Order (1941) instructed troops to summarily execute Soviet political officers captured on the battlefield. The Barbarossa Decree removed legal constraints on soldiers, effectively authorizing the murder of civilians suspected of resistance in occupied Soviet territory. These orders were carried out on a massive scale, contributing to the deaths of millions of civilians and prisoners of war.

It Wasn’t Just the SS

Popular history often isolates the SS as the sole perpetrators of Nazi crimes. While they were certainly at the forefront of genocide, they were far from alone.

Kriegsmarine (Navy)

The German navy, often perceived as “cleaner” than its land-based counterparts, was complicit too. Following the Laconia Incident in 1942, Admiral Karl Doenitz issued the Laconia Order, forbidding U-boat commanders from rescuing survivors, even Allied POWs and civilians, from ships they had sunk. This directive violated international law and cost countless lives.

"1 Efforts to save survivors of sunken ships, such as the fishing swimming men out of the water and putting them on board lifeboats, the righting of overturned lifeboats, or the handing over of food and water, must stop. Rescue contradicts the most basic demands of the war: the destruction of hostile ships and their crews.

2 The orders concerning the bringing-in of skippers and chief engineers stay in effect.

3 Survivors are to be saved only if their statements are important for the boat.

4 Stay firm. Remember that the enemy has no regard for women and children when bombing German cities!”7

Kriegsmarine forces also cooperated with occupation authorities in reprisals against civilians, especially in coastal regions like Greece and Norway.

Luftwaffe (Air Force)

The Luftwaffe conducted terror bombings of cities such as Warsaw, Rotterdam, Belgrade, and London, often targeting civilian infrastructure with the aim of spreading fear. These bombings frequently lacked clear military necessity. Moreover, the Luftwaffe benefited from the Nazi slave labor system. Aircraft production relied heavily on forced laborers and concentration camp inmates, particularly at sites like Mittelbau-Dora, where conditions were so brutal that thousands perished.

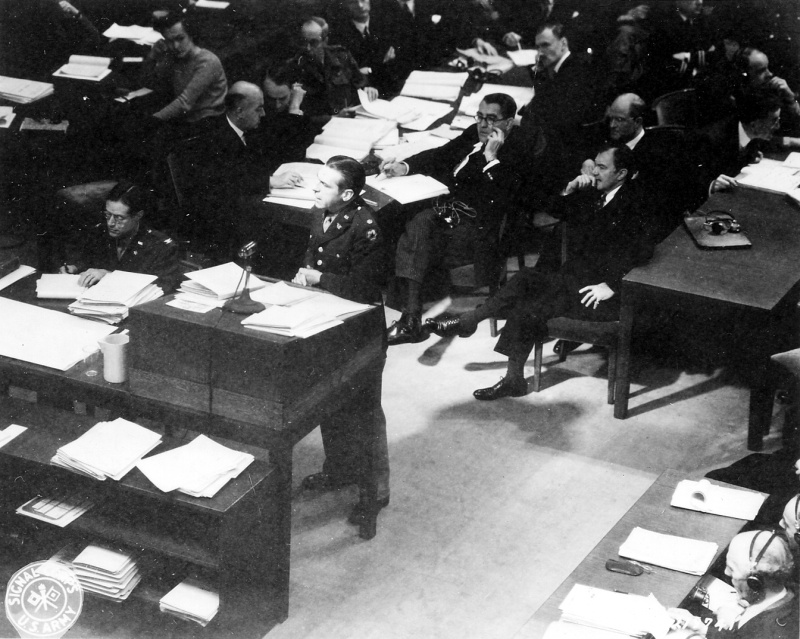

Why Weren’t More Soldiers Prosecuted?

The Nuremberg Trials, while groundbreaking, focused primarily on the Nazi leadership and major war criminals. Only a fraction of those who enabled, committed, or benefited from war crimes were held accountable. The political realities of the postwar period, including the emerging Cold War, led to many prosecutions being dropped or never initiated. Further, prosecuting the tens of thousands of lower-ranking soldiers and officers would have been impossible logistically. The courts simply could not have handled this. As a result, many returned to civilian life with their past largely unexamined and their guilt or innocence unestablished.

A Note of Nuance

Of course, not every German soldier committed war crimes. There were some individuals who resisted, disobeyed, or were simply not in a position to participate in atrocities. But this is not the same as saying that the absence of accusation proves innocence. In a regime where war crimes were systemic, and accountability was exceptional, silence in the historical record often reflects failure of justice, not exoneration.

Conclusion

If we want to understand the full scope of World War II and the Holocaust, we need to reject the myths that absolve entire institutions by default. Scrutinizing the actions of all branches of the German military isn’t about collective guilt, it’s about historical responsibility.

Footnotes

-

Accusation on Merriam-Webster. ↩

-

Conviction on Merriam-Webster. ↩

-

Perpetrator on Merriam-Webster. ↩

-

Samuel de Korte, Tragedy and Betrayal in the Dutch Resistance, Pen and Sword, 2020, 109. ↩

-

David Miller, The Peleus War Crimes Trial, U.S. Naval Institute, February 1997. ↩

-

G. H. Bennett, “The 1942 Laconia Order: The Murder of Shipwrecked Survivors and the Allied Pursuit of Justice 1945-46”, Law, Crime and History (2011) 18. ↩